A Shameful Secret: The Brutal Massacre of the Black Donnellys

In February 1880, a family of Irish Catholic immigrants in Upper Canada were viciously murdered by a group of vigilantes after a bitter feud finally spilled over into violence

Background

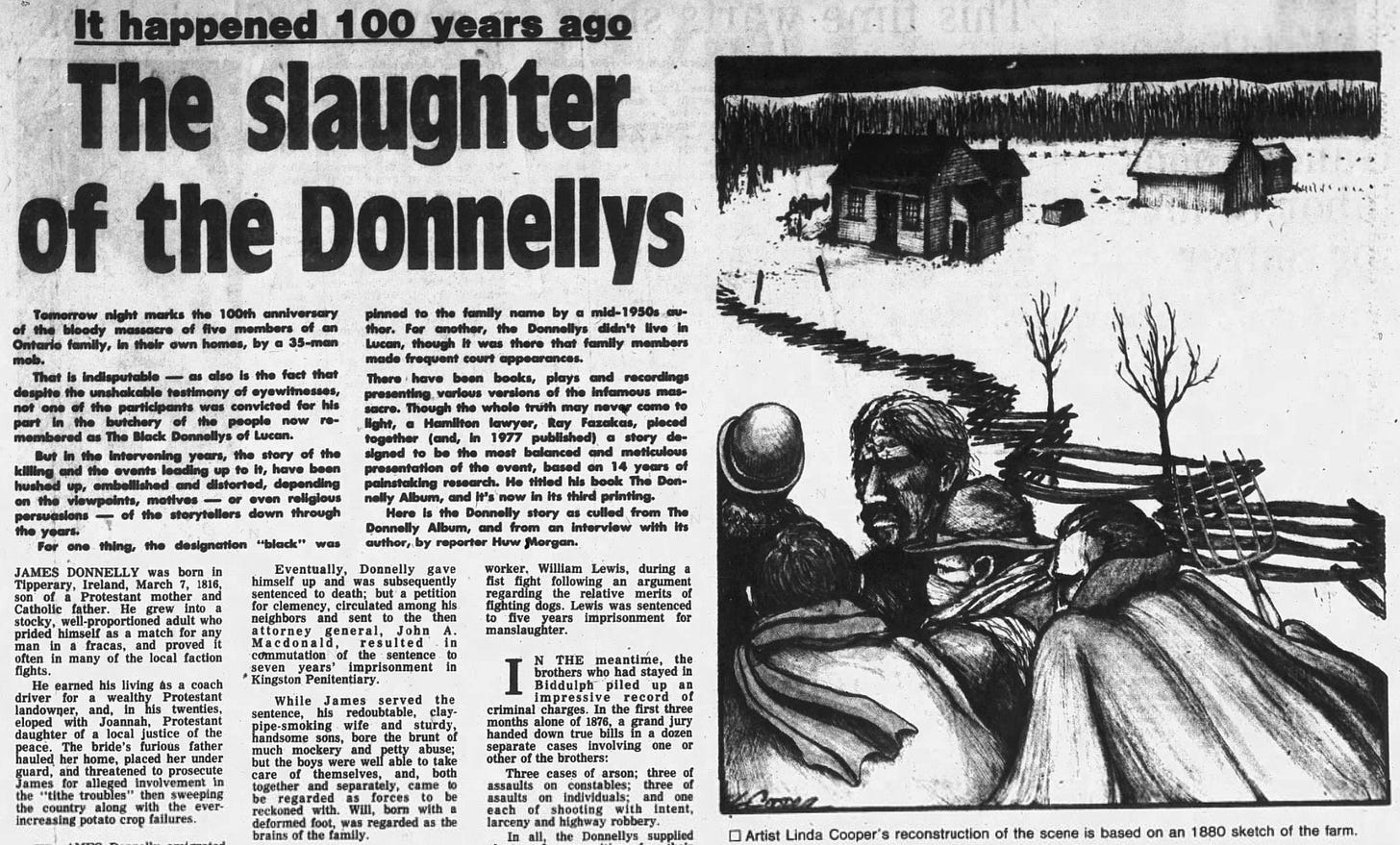

In 1880, citizens of Biddulph Township, a small settlement in Upper Canada (later Ontario), were shocked by the massacre of five members of the Donnelly family. Two women and three men were brutally attacked by a mob intent on vigilante “justice.”

Most of the victims were bludgeoned to death in a drunken frenzy, with even the local constable taking part. For years afterward, the attack was suppressed because many people had relatives who either took part in the attack or were members of the so-called Peace Society.

The Donnellys

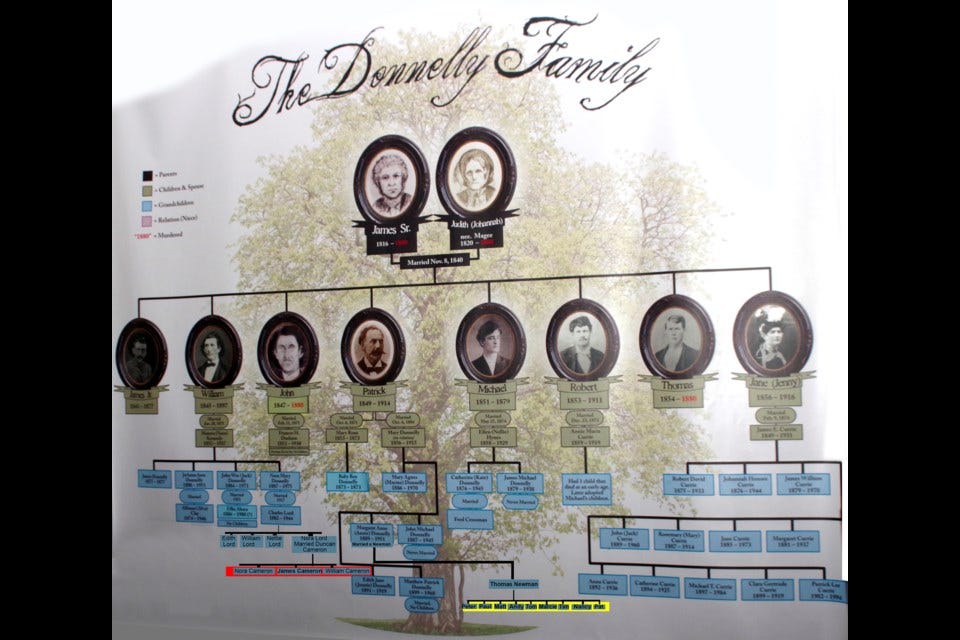

During the Great Famine of the mid-19th century, the Donnelly family, like many of their countrymen, left Ireland for a new start and a better life. The Donnellys were Irish Catholics who settled near Biddulph Township sometime around the 1840’s near a town named Lucan. The family consisted of James, his wife, Johannah, their first son, James, born in Ireland, and seven children born in Canada: William, John, Patrick, Michael, Robert, Thomas, and Jennie.

The Donnellys were known as “Blackfeet” Irish, Catholics who lived peacefully without resisting the English or Protestants. The nickname followed them to Canada, where they were known as the “Black” Donnellys. In contrast, “Whiteboys” were Catholic Irish who opposed English occupation. “Black” Irish were often considered traitors, more despised than Protestants.

The family settled in an area with a high concentration of Irish Catholic immigrants in a predominantly Protestant area. There were already plenty of bitter feelings between the settlers based on religious differences, and the arrival of the Donnellys would further increase tensions.

Growing Tensions

Part of the problem was that the Donnellys settled on land they didn’t own. At that time, many people gained land and farms through “squatting,” the practice of taking over land without legal ownership. The law at the time allowed “adverse possession,” meaning squatters could often gain legal rights to the land by making improvements.

The Donnelly family settled on land belonging to the Canada Company. They worked the land, making improvements, felling trees, and building a home over the next ten years. The only problem was that the land belonged to a man named James Grace. Another immigrant, Patrick Farrell, leased part of the land from the Donnellys.

In 1856, Grace wanted his land back. He brought an ejectment to the Court of Common Pleas in Huron County. His claim was that both the Donnellys and Farrell were squatting on his land. The judge recognized the years of the Donnellys’ work and granted them fifty acres. He split the rest of the lot to Patrick Farrell, leading to bitter feelings.

Imprisonment of James Donnelly

On June 27, 1857, violence erupted during a barn-raising. James Donnelly (the father of the clan) and Patrick Farrell got into a fist fight. Farrell suffered a blow to the head and died two days later. Fearing the worst, James went into hiding. He managed to evade the law for two years until he eventually surrendered. A judge sentenced him to hang for the murder of Farrell.

His wife, Johannah, fearing to face life alone with eight children, petitioned the courts for clemency. To her relief, and James’, the sentence was reduced to seven years in the Kingston Penitentiary.

While James was in prison, his sons began to develop a bad reputation among local law enforcement, allegedly being involved in numerous assaults and altercations.

Stagecoach Feud

In 1873, the Donnelly brothers, William, Michael, John, and Thomas, began a stagecoach line that quickly outrivaled any other stage line in the area. Soon, other stage lines began to feel pressure from the competition. In October 1873, Hawkshaw Stage Line sold out to Patrick Flanagan, a man determined to drive the “Black” Donnellys out of business.

Shortly after, the great “Stagecoach Feud” began. Stages were smashed or burned, horses beaten or killed, stables burned to the ground. While most of the violence was blamed on the Donnellys and gave the family a further bad reputation, there were few, if any, actual convictions.

Although there were few formal charges, the Donnellys were a source of constant friction in the area.

Peace Society Vigilantes

In June 1879, Father John Connolly, the priest at St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, hoped to ease some of the tensions in the area. He established a Peace Society Association in Biddulph and invited everyone to pledge their support. One condition he set was that anyone who joined would consent to having their homes searched for stolen property. To no one’s surprise, the Donnellys refused.

This caused the Donnellys to leave St. Patrick’s and join another nearby church. They viewed Father Connolly as part of the problem rather than the solution. James and his family disagreed with Father Connolly’s hardline anti-Protestant stance, as many of the Donnellys ’ friends and neighbors were Protestant.

In August 1879, a militant splinter group broke away from the Peace Society. They became known as the Vigilance Committee Society. Most members, including Constable James Carroll, had strong grievances against the Donnelly family.

On the evening of February 3, 1880, the members of the Vigilance Committee gathered at the Cedar Swamp Schoolhouse in Biddulph. Earlier that month, a man named Patrick Ryder’s barn burned down. Like many arsons in the area, the Donnellys were blamed, though there was no evidence to confirm this.

Father Connolly of St. Patrick’s Church offered a reward for any guilty parties to be found and punished. But this didn’t go far enough for the members of the Vigilance Committee. They decided to take the law into their own hands.

Several of the Donnelly sons had been seen at a wedding when Ryder’s barn burned. Their father, James Donnelly, sent a letter to a lawyer in London, Ontario, who would defend them in the case against Mr. Ryder. James planned to file countercharges against Ryder.

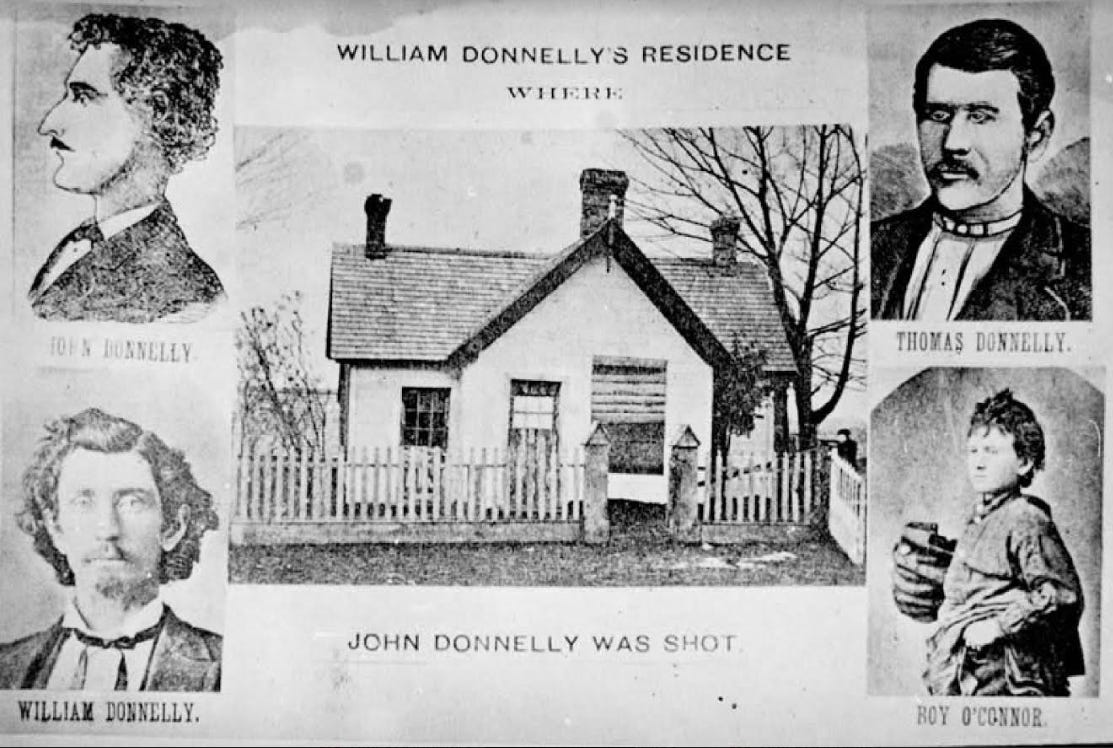

After mailing his father’s letter, John Donnelly left to spend the night with his brother, Will, who promised to loan the family a cutter to travel to the trial the next day. The trial was scheduled for February 4th.