"Forgiveness is the Ultimate Revenge": The Execution and Exoneration of John Gordon

In February 1845, Irish immigrant John Gordon became the last man executed in the state of Rhode Island. More than 165 years later, his name was finally cleared when he was officially pardoned

Background

In the spring of 1844, Irish immigrants John Gordon and his brothers William and Nicholas stood trial for the brutal murder of one of Rhode Island’s most prominent citizens, a wealthy industrialist named Amasa Sprague.

From the start, the trial and its coverage were tainted with overt anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudice. The jury was instructed by the judge to give more weight to Yankee witnesses than Irish witnesses.

The judge did not attempt to mask his bias. He sustained nearly every objection raised by the prosecution and overruled almost any objection brought by the defense. Even with this sham trial, only one of the defendants, John Gordon, was found guilty.

On February 14, 1845, he became the last person to be executed in the state of Rhode Island. Seven years later, in 1852, Rhode Island abolished capital punishment, due in part to the circumstances surrounding Gordon’s execution.

Arrival in America

John Gordon’s older brother Nicholas was the first member of the family to come to America, arriving in 1836. Intent on making a better life for himself and his family, Nicholas rented space and opened a store. He used the profits to purchase some land where he built his own store along with a second-floor apartment in Spragueville.

His business increased significantly when he obtained a license to sell alcohol by the bottle. Later, he applied for and was granted a tavern license, which enabled him to sell alcohol by the glass.

The success of his business allowed Nicholas to obtain passage to America for his family back in Ireland. In June 1843, his mother, sister, niece, and three brothers joined him in Rhode Island.

The Spragues

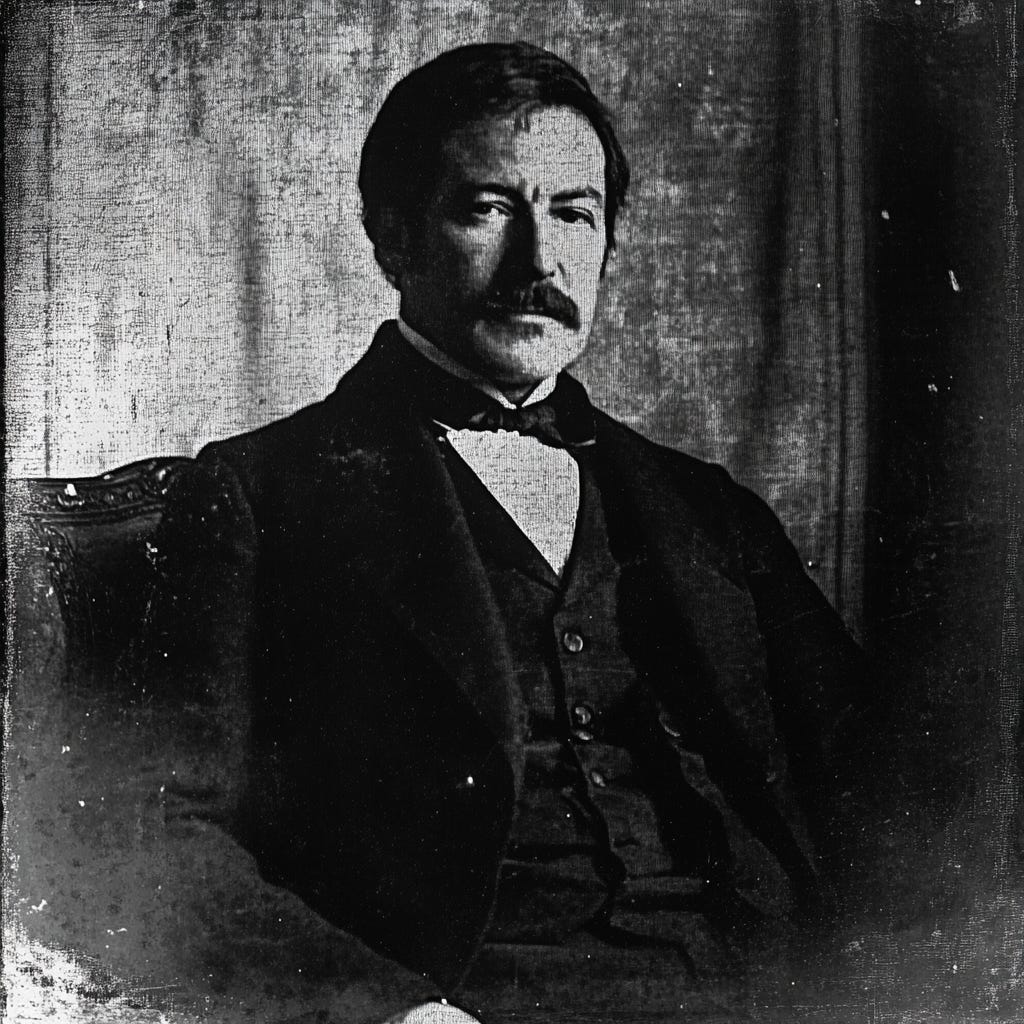

The Sprague family was one of the most prominent and influential in the state. Amasa Sprague and his brother William owned several mills, including A&W Sprague Mill in Cranston, Rhode Island, which Amasa oversaw.

William Sprague was also a U.S. Senator and former Governor. They also had other family members in the state legislature and local politics. Needless to say, the family had enormous political influence.

Amasa’s wealth and political connections gave him free reign to run his mills as he saw fit, which meant exploiting hundreds of uneducated and impoverished Irish men, women, and children.

He owned the mill, company houses, and the company store, and paid his employees with credit that could only be used at the company store or rent for the company houses. This kept his employees indebted to the mill in a neo-feudal arrangement.

Conflict with Nicholas Gordon

Nicholas Gordon was one of the few Irishmen in the area who was not under the thumb of Amasa Sprague. However, in the summer of 1843, the two would clash.

Sprague had become irritated that many of his employees were drinking before and sometimes during work hours, which had led to an increase in accidents and a decrease in production.

He blamed Nicholas Gordon and his establishment. Sprague used his political influence to deny Gordon’s liquor license renewal, greatly reducing his income.

Some witnesses reported that Gordon threatened Sprague, though this has been contested.

Murder of Amasa Sprague

On December 31, 1843, Amasa Sprague left his mansion to check the livestock on a farm he owned in neighboring Johnston.

Several hours later, Sprague’s battered body was discovered by a handyman returning from work at the mansion. Sprague had been beaten so savagely that at first, the employee did not even recognize him.

Sprague had been shot in the forearm and pistol-whipped so ferociously that the gun had broken apart and been left at the scene. The brutality of the crime and the fact that cash and a watch were left on the body seemed to rule out robbery as a motive.

Gordon Brothers Indicted

Despite a lack of any evidence or eyewitnesses, Nicholas Gordon was arrested the day after the murder. John and William were indicted for the murder, while Nicholas was charged with being an accessory before the fact. Nicholas had been attending a Christening in Providence at the time of the murder.

Immediately after the murder, biased newspapers like the Providence Journal ran disparaging articles about the Gordon family in an attempt to sway public opinion.

The Gordons had the support of the local Irish and Italian immigrant communities, as well as the labor and workers’ rights movements.

Investigation and Trial

William Sprague resigned from the Senate to head the investigation into his brother’s murder, creating a massive conflict of interest. Rather than being held at the Sheriff’s office, collected evidence was stored at the Sprague mansion.

In a blatant show of bias, the presiding judge, Chief Justice Job Dufree, instructed the jury to give more credence to the testimony of the prosecution’s witnesses. Any evidence that was unfavorable to the prosecution was excluded.

Many of the witnesses for the prosecution contradicted one another. A local prostitute who supposedly knew the Gordon brothers testified against them despite misidentifying William as John.

An unidentified coat that was found at the crime scene was said to belong to John, even though it was at least two sizes too big for him.

All of the “evidence” against the Gordon brothers was entirely circumstantial, with the primary piece being the gun that was found at the scene. It was known that Nicholas Gordon owned a handgun he kept in his store for protection.

After the murder, the gun went missing. The prosecution argued that the missing gun must have been the murder weapon used by the Gordons.

Nicholas, who had been tried separately, had a hung jury and was scheduled to be tried again after the conclusion of his brothers’ trial. Despite the unfair nature of the trial, on April 17, 1844, William Gordon was found not guilty.

However, 29-year-old John Gordon, who was prone to alcoholic blackouts and did not have an alibi at the time of the murder, was found guilty. His execution was set for February 1845.

Then, weeks before John was set to be executed, William Gordon made a startling confession. William admitted to taking Nicholas’s gun and hiding it out of fear. He then turned it over to the authorities.

Despite the clear proof that this was not the gun used to kill Sprague, as that gun had been broken and left at the scene, this new information was not allowed to be presented in court, and was not reported on by the anti-Irish Catholic newspapers.

With this revelation, Gordon’s attorney, John Knowles, filed a petition with the appeals court, which also happened to be the State Supreme Court that had just tried the case. This was another blatant conflict of interest.

The state legislature - which was controlled by the Sprague family - refused to postpone John’s execution until Nicholas’s second trial was concluded to see if a conspiracy was proven.

After exhausting all petitions and appeals, John Gordon was hanged in the yard of the state prison in Providence on February 14, 1845. In his final words, he cited the words of Jesus saying, “I forgive them for they know not what they do.”

Aftermath

John Gordon’s funeral was attended by Irish communities and supporters from all over Rhode Island and neighboring states.

Though he was later freed after another deadlocked jury, by then Nicholas Gordon was a broken man. The stress of imprisonment and the ruin of his family had taken its toll. He began drinking heavily and died eighteen months later.

Seven years later, due in large part to the travesty of the trial and execution of John Gordon, the state of Rhode Island became one of the first states to abolish capital punishment.

Though it was later amended in 1873 to allow the death penalty for murders committed while incarcerated, no one was executed, and in 1984, the General Assembly removed the death penalty from the Penal Code.

The story of John Gordon has inspired several literary works, including the book “The Hanging & Redemption of John Gordon, The True Story of Rhode Island’s Last Execution,” Written by author Paul Caranci.

It was also the basis for the 2011 play “The Murder Trial of John Gordon,” written and directed by Ken Dooley. In fact, this play helped spark the legislation that led to the posthumous exoneration and pardon of John Gordon.

On June 29, 2011, a ceremony was held during which John Gordon was officially pardoned. The legislation had been initiated by State Representative Peter F. Martin and Senator Michael J. McCaffrery, and was signed by Governor Lincoln Chafee.

“Today, we have righted a wrong, and we have done the just thing,” said Representative Martin.

In October, 2011, a memorial headstone was erected for Gordon, reading “Forgiveness is the Ultimate Revenge.’’

Sources:

“Rhode Island.” Death Penalty Information Center, 2025, https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state/rhode-island

“Personal papers of 19th century judge shed light on last R.I. trial to end in execution.” Rhody Today, The University of Rhode Island, 2025, https://www.uri.edu/news/2008/06/personal-papers-of-19th-century-judge-shed-light-on-last-r-i-trial-to-end-in-execution/

Dooley, Ken. “John Gordon.” Small State Big History, The Online Review of Rhode Island History. 17 September 2021, https://smallstatebighistory.com/john-gordon/

Caranci, Paul. “The Execution of John Gordon, a Victim of Anti-Irish Catholic Prejudice.” Small State Big History, The Online Review of Rhode Island History. 24 September 2021, https://smallstatebighistory.com/the-execution-of-john-gordon-a-victim-of-anti-irish-catholic-prejudice/