Kidnapped in Philadelphia: The Tragic Abduction and Disappearance of Charley Ross

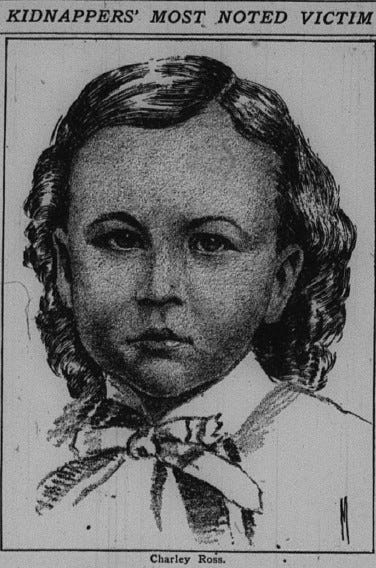

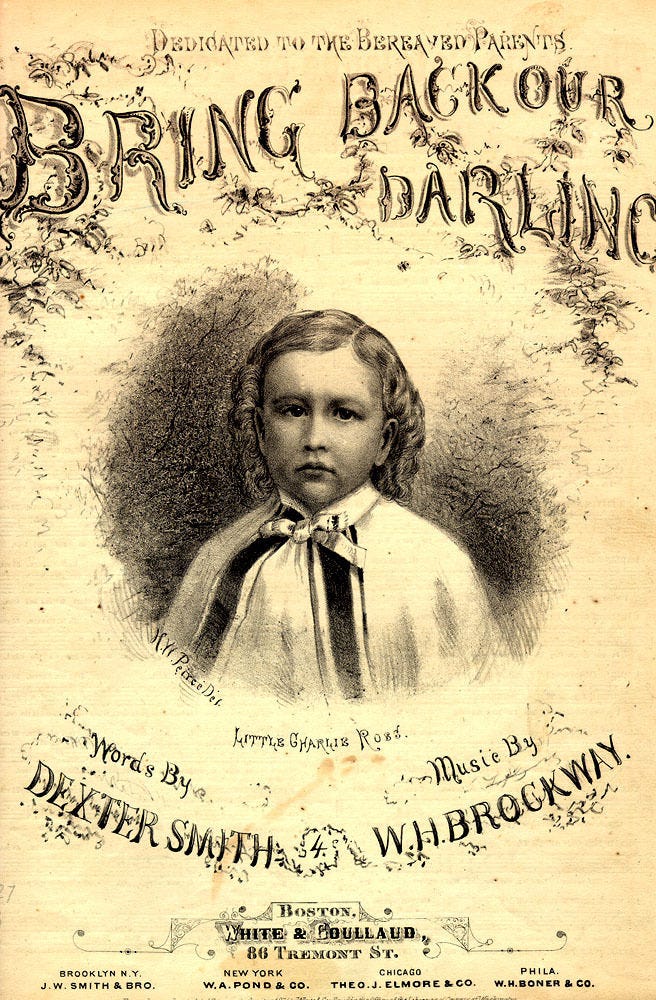

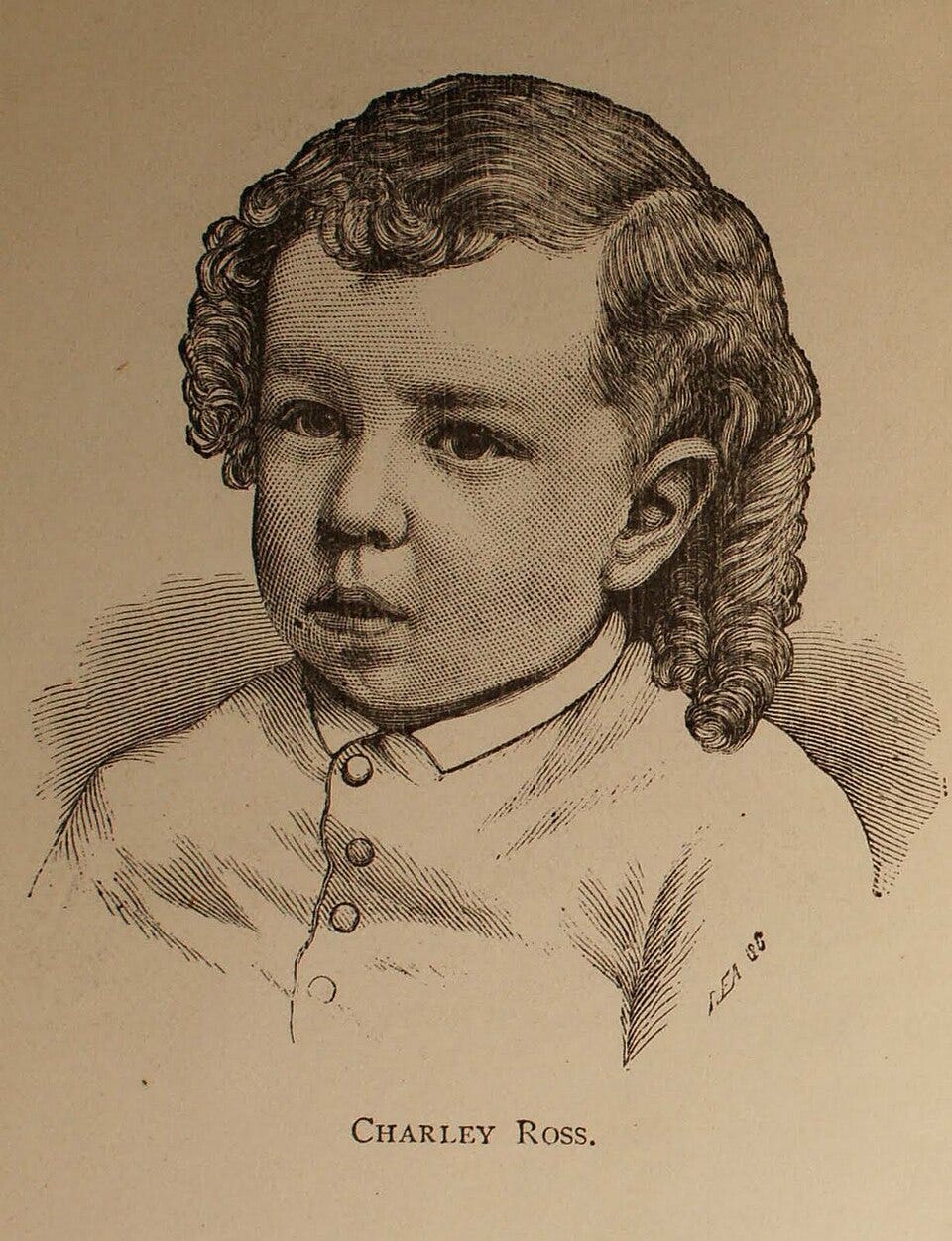

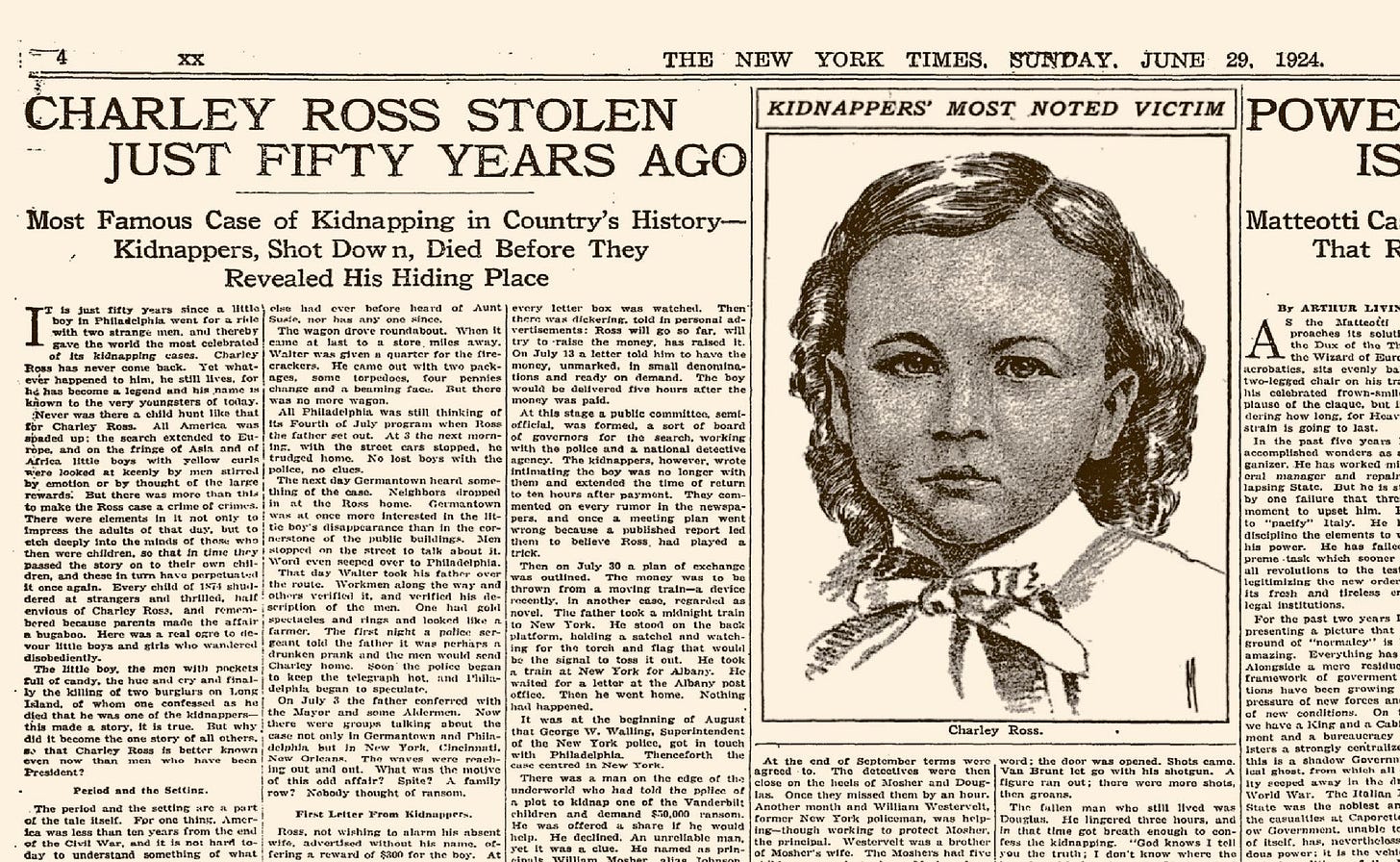

In July 1874, four-year-old Charley Ross was kidnapped from his Philadelphia neighborhood by two strangers. Despite the case's national notoriety, young Charley was never located

Background

On July 1, 1874, Four-year-old Charley Ross and his six-year-old brother, Walter, went out to play in the front yard of their home in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. Two men approached in a buggy and offered to take the boys to buy firecrackers and candy. An hour later, Charley Ross vanished forever. To this date, Charley’s fate remains unknown and is one of the most famous disappearances in U.S. history.

Abduction of Charley Ross

In 1874, the Christian K. Ross family lived on East Washington Lane in Germantown, a wealthy section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Mr. Ross and his wife had seven children, including Walter, aged six, and his younger brother Charley, aged four. The two brothers were constant companions and often played together in the front yard of their spacious home.

On June 27, as the boys played outside, two men in a buggy pulled up to talk to them. They asked the boys if they liked candy. Both Walter and Charley said they loved candy.

The men offered them some, talked a little more, and then left. Over the next few days, the men returned, gave the boys a treat, and talked in a friendly fashion. Walter and Charley began to look forward to the men’s visit. They were no longer “strangers” offering candy, but trusted friends.

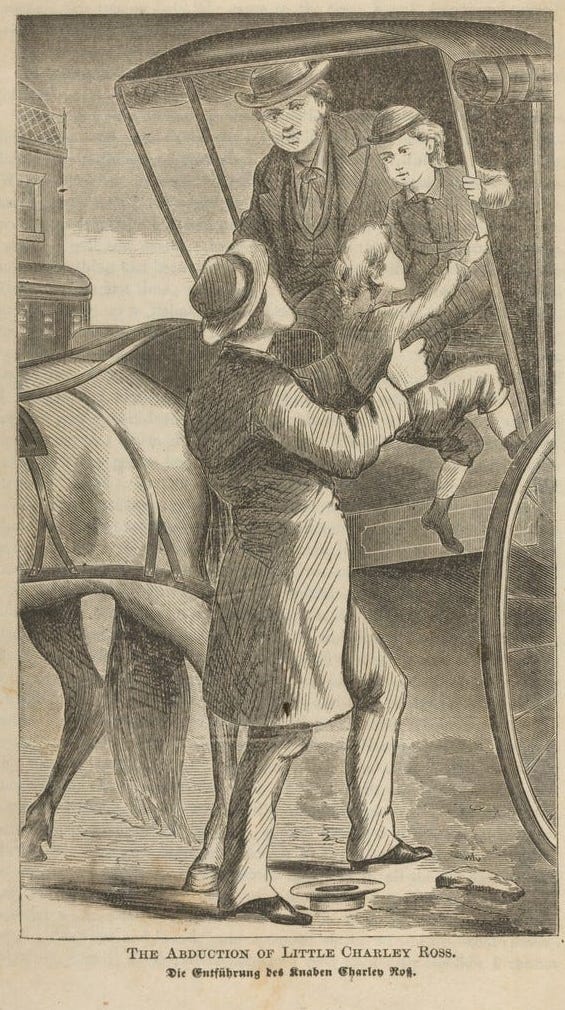

On the morning of July 1st, Charley and Walter were playing outside. The boys were eagerly awaiting the upcoming Fourth of July holiday. To their delight, their friends in the buggy stopped to talk.

They offered to take the boys to a nearby store to buy candy and firecrackers. Walter and Charley climbed into the buggy. The men drove to a neighborhood store, where one of them gave Walter twenty-five cents to go inside and buy firecrackers.

A few minutes after making his purchase, Walter walked outside. To his shock, the carriage, with Charley inside, was gone. Frightened, Walter ran to a stranger for help. The man took him home to share the terrible news with his family.

Christian Ross was beside himself. He couldn’t understand why someone would take his son. Although he owned a dry goods store and people might have assumed he was a wealthy man, that was not the case. The truth was, Mr. Ross had lost almost all his money in the stock market crash of 1873. He had no money to pay a ransom.

Over the next few days, people offered several theories about Charley’s abduction. One suggested that Mr. Ross himself had arranged the kidnapping for notoriety, although no one could say exactly why he would do such a thing. Christian Ross did his best to keep the tragic event from his wife, who was recuperating from an illness in Atlantic City. She would later learn the tragic tale when her husband began advertising in newspapers for the safe return of their son.

Another theory put forward seemed equally unlikely: gypsies had stolen the child. Walter Ross, who was old enough to describe the men, put this theory to rest by saying the men were not gypsies. Others thought a relative might have taken Charley to play a “joke” or to “gift a childless couple with a son.”

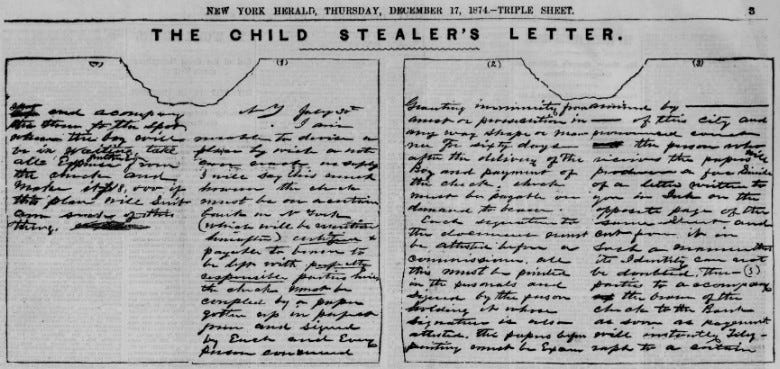

Ransom Notes

Two days later, on July 3, the first ransom note arrived. The first few ransom notes were mailed from post offices in Philadelphia and nearby towns. Each one was written in a semi-literate style, with many spelling errors and coarse language. The first note read as follows:

July 3 – Mr. Ros be not uneasy you son charly be all writ we is got him and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand. You will hav two pay us before you git him from us and pay us a big cent to. If you put the cops hunting for him you is only deefeting you own end.

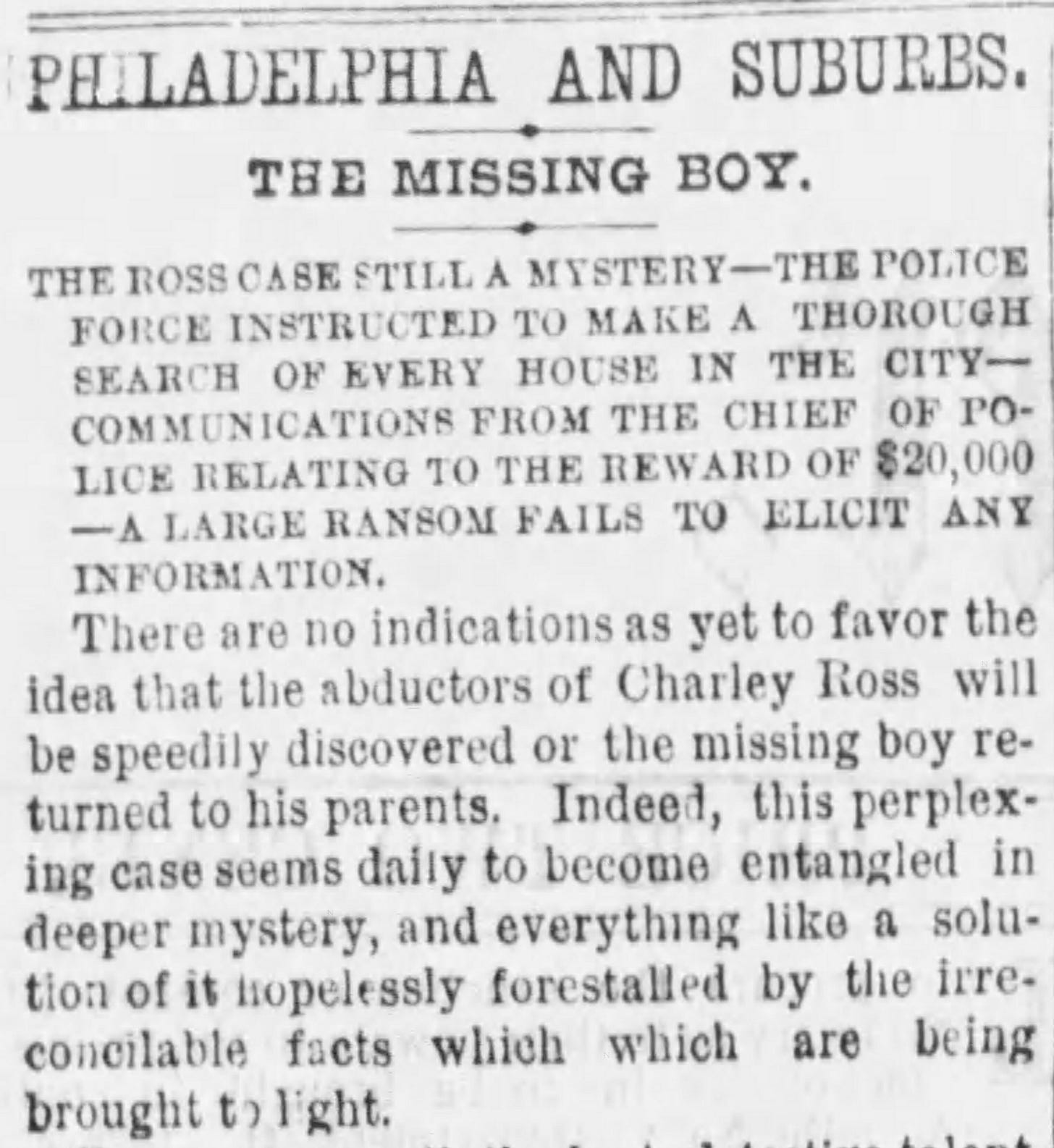

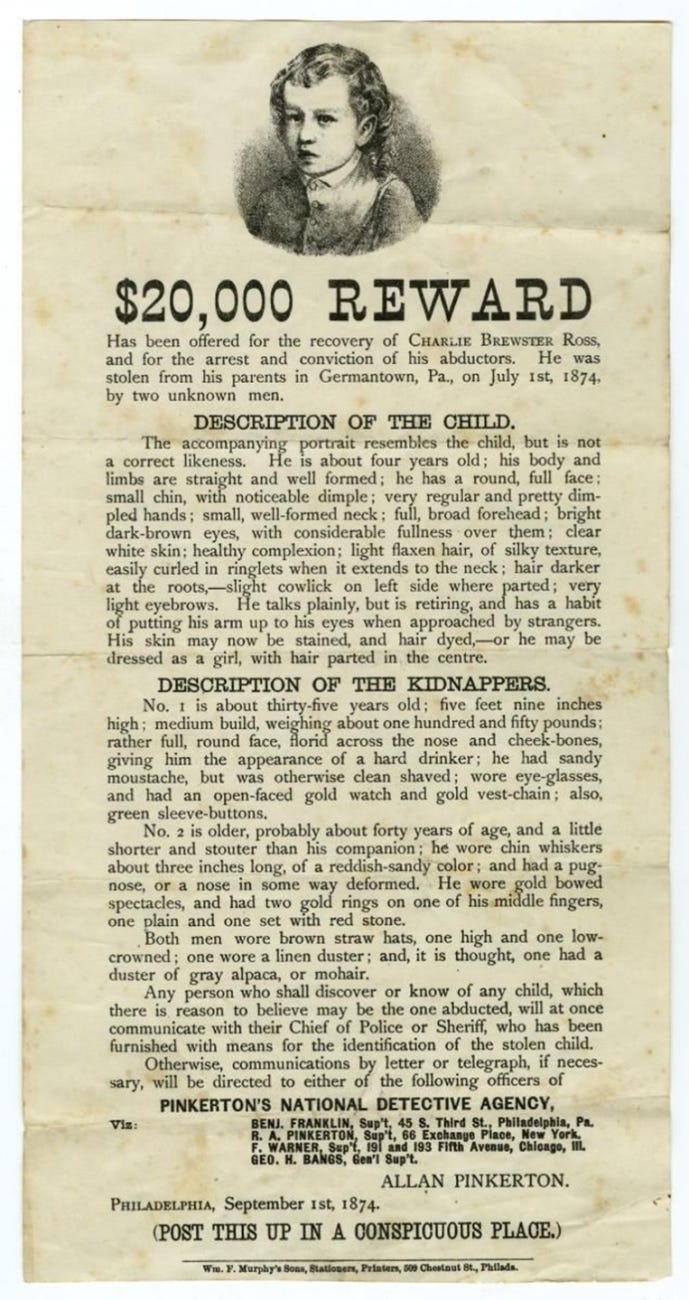

The note told Mr. Ross he would be hearing from them in a few days. On July 7, he received a ransom demand for $20,000 (roughly $400,000 in today’s money). Even though the notes cautioned against going to the police, Mr. Ross had no choice. He didn’t have the ability to pay any of the ransom on his own. Someone had Charley, and he needed help finding him.

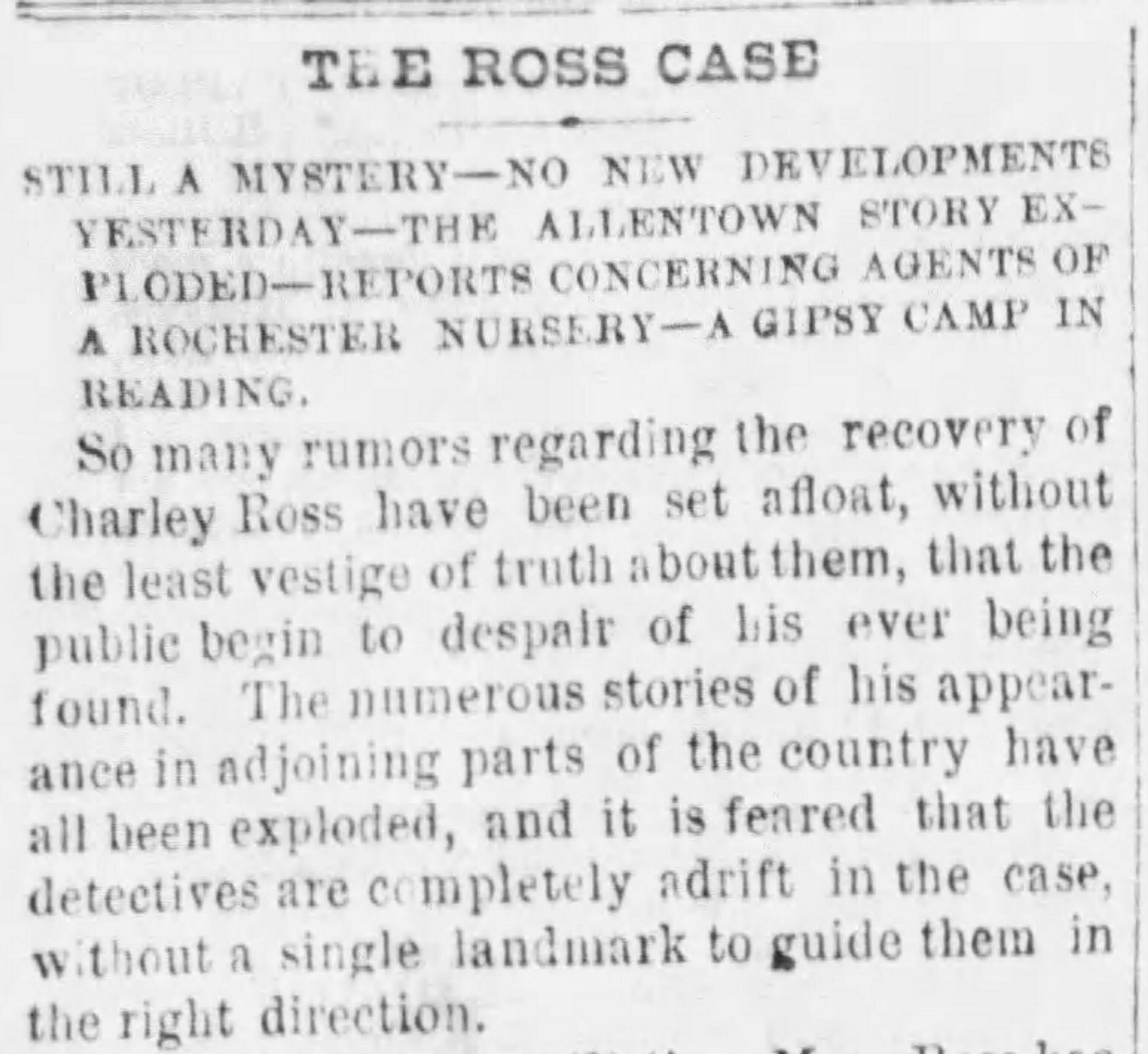

Over the next several months, Mr. Ross received twenty-three letters, assuring the family that Charley would be safe if their demands were met. Mr. Ross was instructed to put personal ads in the Philadelphia Ledger to respond to the kidnapper’s demands. Unable to raise the money, he kept trying to stall the kidnappers.

On July 22, after days of excruciating fear, Mr. Ross finally agreed to meet the kidnapper’s demands. On July 30, the kidnappers told Mr. Ross to paint a valise white, put the $20,000 inside, and take a certain train to New York. If he saw a given signal, he was to drop the valise on the tracks. Although he did as instructed, he saw no signal. The kidnappers later accused him of not taking the train.

On another occasion, Ross posted an ad requesting a simultaneous exchange of money for Charley. His request was denied.

Response

Unable to raise the money on his own, Mr. Ross made the decision to seek help from the Philadelphia police. The police began an intensive search for the missing boy. They found witnesses who had seen both boys in a buggy and watched Walter enter the store alone. However, no one had seen the buggy leave or knew what direction it had gone.

In their efforts to find Charley, the police set aside any lawful considerations in their search of private property. They scoured the city, continuing even when people grew angry and didn’t want them to search. This resulted in the police finding and recovering plenty of stolen merchandise. Several criminals were arrested and jailed, but there was still no sign of Charley.

Other wealthy families began to keep their children shut inside, fearful of becoming victim to a similar crime. The case soon became national news and received widespread media coverage from coast to coast.

Several other agencies—such as Pinkertons—were also on the lookout for Charley. Even Barnum, of Barnum and Bailey Circus fame, offered to help find the kidnappers. He had only one condition: If he found the boy, Mr. Ross must allow Charley to travel with the famous circus as a sideshow attraction.

Although Mr. Ross agreed, even the widespread abilities of the great Barnum could find no leads to the kidnapped little boy.

A Suspect Emerges

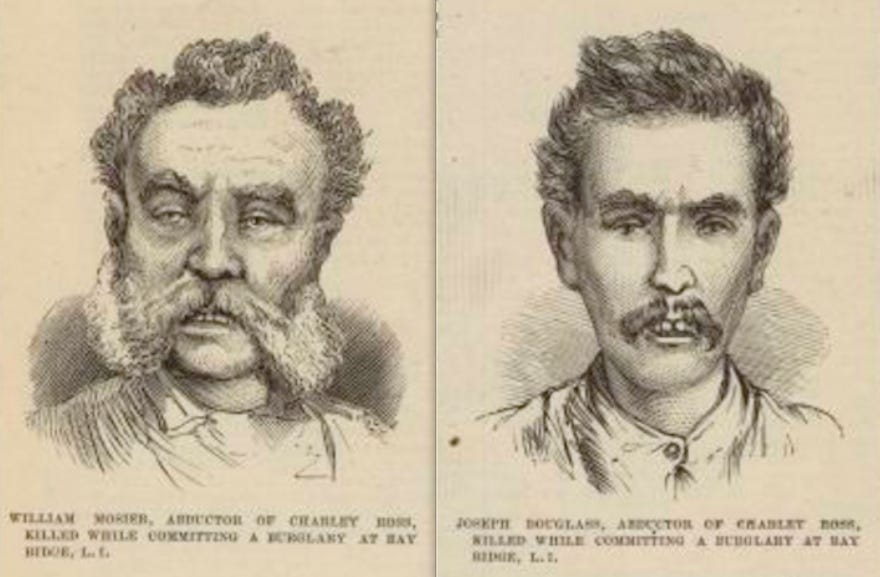

It wasn’t until August 2 that there was a break in the case. Chief of Police George Walling of New York asked to see one of the original ransom notes. He had been involved in a similar case when someone tried to kidnap one of the Vanderbilt children. The handwriting appeared to resemble that of a man named William Mosher, a fugitive convict.

The Pinkertons tried their best to find Mosher, and although they had several leads, they weren’t able to pin him down. The trail went cold until November 22, when Mr. Ross received the final note from the kidnappers.

He was instructed to take a room at a hotel in New York. He was to bring the money, and someone would come to his room to pick it up. The kidnappers insisted that the person picking up the money would have no involvement with the crime, so there would be no use in following him. Once the kidnappers had the money, Charley would be released. However, no one showed up. Mr. Ross went home with the money, but without Charley.

Then, on December 14, 1874, a large unoccupied summer home in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, belonging to Judge Charles Van Brunt, was broken into. Unbeknownst to the would-be robbers, the home had a burglar alarm connected to the home next door, which belonged to Charles’ brother, Holmes Van Brunt.

When Holmes heard the alarm bells ringing, he at first believed the wind might have blown a window open, triggering the alarm. He sent his son Albert to investigate. As Albert proceeded towards his uncle’s mansion, he saw movement from inside. He quickly returned and alerted his father.

Holmes, Albert, and two of their hired men quickly armed themselves and made their way next door. Albert and one man stood guard at the front door, while Holmes VanBrunt and the other man went to the rear. Shortly afterward, two men came out of the cellar. Holmes VanBrunt yelled, “Halt!” Suddenly, the men fired at him and his hired man. Holmes fired back, injuring one of the men.

The second burglar fled and ran around to the front of the house. Albert, alerted to the danger by his father, fired. The burglar returned fire, and Albert shot him in the chest and killed him. At the rear door, Holmes and the hired hand were also in a gun battle. The second burglar seemed determined not to go down without a fight.

A Startling Confession

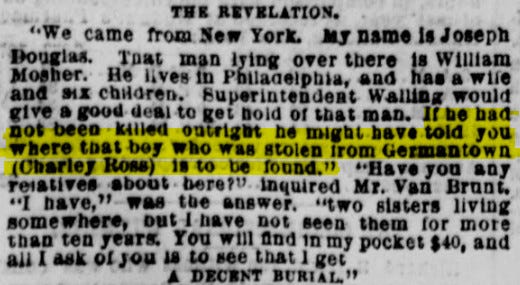

The burglar was hit multiple times, and as he lay dying, he made a startling confession. He confessed to Holmes that his name was Joseph Douglas. The other man with him was William Mosher. “We kidnapped a boy named Charley Ross for the money,” he said. Holmes had read the newspapers and was familiar with the case. He asked the obvious question. “Where is Charley?”

Douglas said that only Mosher knew the boy’s whereabouts. No one else. When the men told him Mosher was dead, Douglas demanded to see the body. Albert and the hired man dragged William Mosher’s body to the backyard.

Douglas insisted that with Mosher dead, Charley would be returned safely within a few days. He asked the men to see that he was buried with the last $40 in his pockets, money he had earned legitimately. Minutes after his confession, Douglas died.

Young Walter Ross, Charley’s brother, was taken to identify the bodies. He positively stated these were the “friends” who had taken them for a ride in the buggy. Walter especially remembered the “monkey nose” of Mosher, who had a cancer-related deformity.

Other witnesses also identified them as the men in the buggy on that fateful day. Mosher’s wife, when questioned by police, said she knew her husband had kidnapped Charley but did not know where he had taken the boy or even if he was still alive.

The kidnappers had been identified, but Charley was still missing.

Aftermath

In an effort to reunite Charley Ross with his family—if he was still alive— on February 25, 1875, the Pennsylvania legislature added a special provision to the law defining kidnapping. If anyone currently had a kidnapped child within their care, they would not be prosecuted if they returned the child to a sheriff or magistrate by March 25, 1875.

Mr. Ross also offered a $5,000 reward for information. The reward was never claimed, and despite the case's high profile, Charley was never returned.

A former Philadelphia policeman, William Westervelt, was later arrested and held in connection with the case. He had been a friend and confidant of William Mosher. Hoping to find Charley, police charged Westervelt in 1875 and tried him for kidnapping.

However, the police found no evidence linking him to Charley’s disappearance. Charley’s brother, Walter, insisted he had never seen Westervelt in the buggy or anywhere near their “friends.” Westervelt was found not guilty of kidnapping but charged with a lesser crime of conspiracy. He served six years in prison and always maintained his innocence.

Two years after Charley’s kidnapping, Christian Ross published a book, The Father’s Story of Charley Ross, the Kidnapped Child. He hoped to raise money to continue the search for Charley. In 1878, to renew interest in Charley’s fate, Mr. Ross reprinted his book and gave lectures in Boston.

Until Christian’s death in 1897 and his wife's death in 1912, the couple continued to search for Charley. Through the years, they interviewed over 570 boys and—eventually—men who claimed to be Charley. All were impostors. The Rosses printed posters, followed every lead, and spent over $60,000 to find Charley.

The 50th anniversary of Charley’s kidnapping in 1924 brought a new crop of newspaper stories. Walter, then an adult, said he and his sisters still received letters from men who claimed to be their long-lost brother.

In 1939, a court in Arizona declared a man named Gustave Blair to be the real Charley Ross. The remaining members of the Ross family refused to acknowledge him, and in the era before DNA, it was impossible to definitively prove or disprove the claim.

Despite the sad ending to Charley’s story, his kidnapping became national news, with thousands of people invested in the outcome. This case had a profound impact on how kidnapping cases are handled to this day. Charley Ross was never found, but his memory lives on.

Sources:

23 letters: A Child Lost Forever. (n.d.). Pennsylvania Center for the Book. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/23-letters-child-lost-forever

Duke, Thomas. “The Kidnapping of Little Charley Ross 1874.” HistoricalCrimeDetective.com. (n.d.). https://www.historicalcrimedetective.com/the-kidnapping-charley-ross-

Thomas, Heather. “The Kidnapping of Little Charley Ross.” Headlines & Heroes, 23 April 2013, The Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2019/04/the-kidnapping-of-little-charley-ross/

Since most child disappearances are not kidnappings, most child kidnappings are not murders, and most child murders are not sexually motivated (indeed rape is about sex not power) this indicates that it was a gang of kidnappers working for the Irish mob. Because the kidnappers were killed the Irish mob moved Charley (I wish people spelt names right) repeatedly, used him as a butler, and tried to indoctrinate him as an associate (but since he was a Presbyterian it didn't work, but he was trained as an associate, which would be useful for a butler). Remember mamluks and janissaries were slaves but did not betray their masters until the Mamluks took over Egypt under the Pashas. DNA work needs to be done.