The Apache Kid: How A Respected U.S. Cavalry Indian Scout Became A Notorious Fugitive

In 1887, a controversial incident would forever alter the life of a highly regarded cavalry scout known as the Apache Kid, causing him to go from assisting the U.S. military to being hunted by them

Background

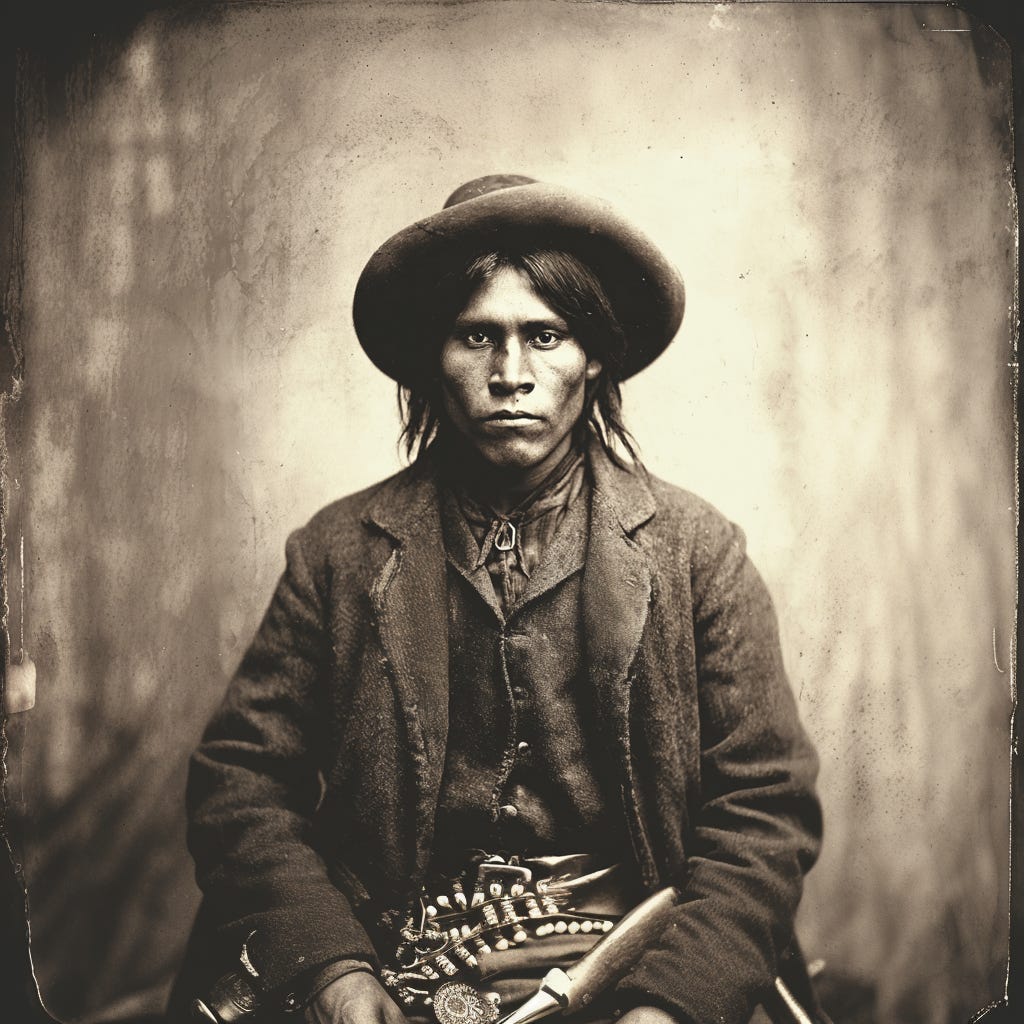

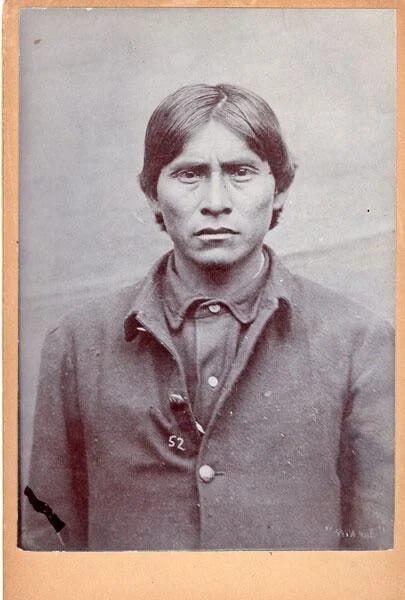

His birth name - Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl – was too difficult to pronounce, so he became known as the Apache Kid. A respected scout for the U.S. government, until an act of violence turned him into a notorious renegade. In 1889, while being transported to a territorial prison, he escaped, becoming a wanted fugitive.

Rumors of sightings persisted for decades; however, he was never found. His fate remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of the Wild West.

Early Years

Born around 1860, in the rugged heart of Aravaipa Canyon, Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl—later known as the Apache Kid—emerged from the “Dark Rocks People,” a subgroup of the Western Apache. His name, difficult to pronounce but hauntingly prophetic, meant “tall man destined to come to a mysterious end.” A mystery that would follow him all his life and after.

As a boy, the Kid learned English and worked odd jobs around the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. His intelligence and quiet strength caught the attention of famed scout Al Seiber, who took him under his wing. By 1881, the Kid had enlisted in the U.S. Army’s Indian Scouts, part of the “SI” Band. His tracking skills and knowledge of the land made him a great asset.

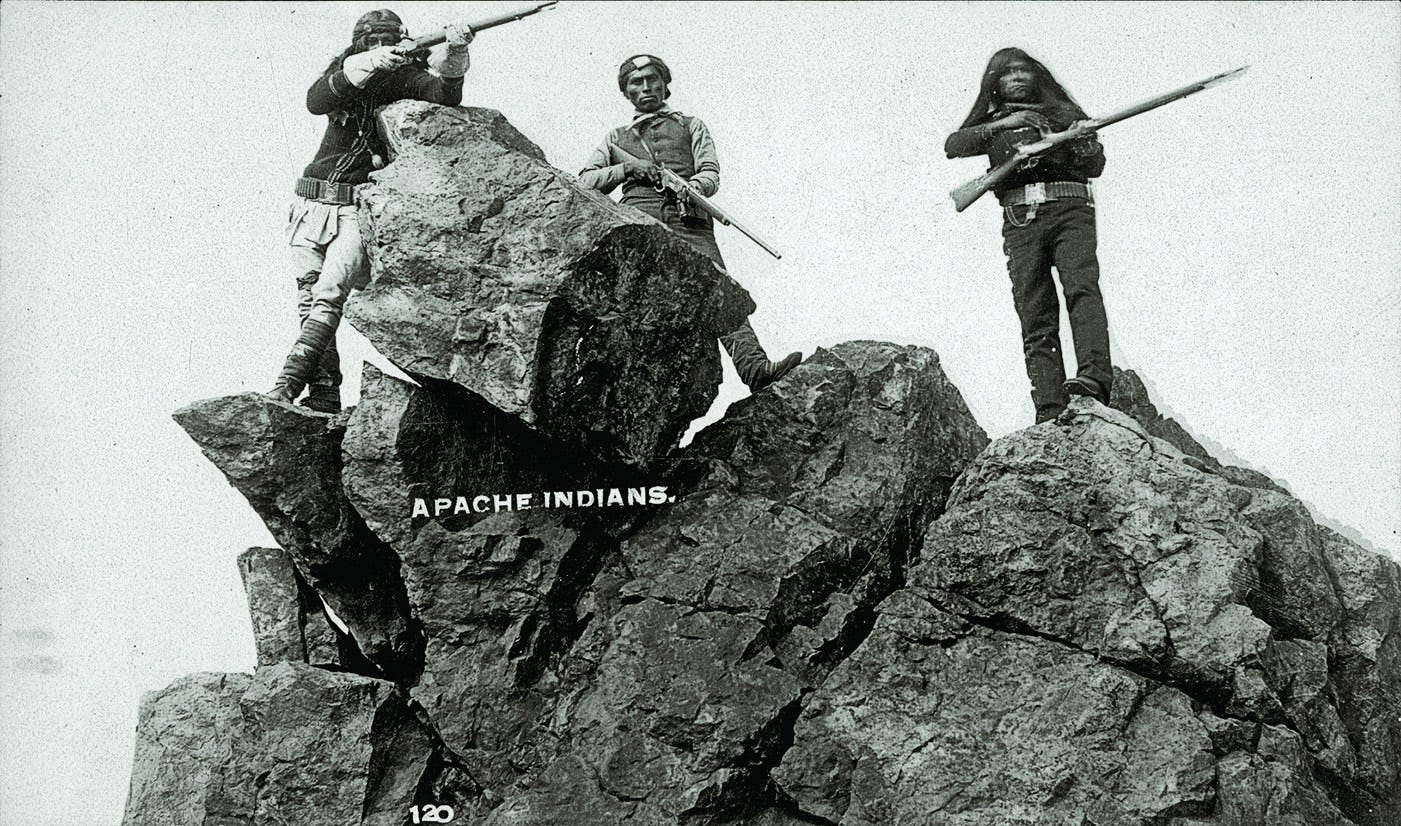

At the time, tensions between settlers and Apache were high. General George Crook, seeking a strategic solution, began recruiting “friendly” Apache to help locate and suppress raiding parties. The Kid, loyal and skilled, became one of Crook’s most trusted scouts. In July 1882, he was promoted to sergeant and later accompanied Crook on expeditions deep into the Sierra Madre.

By the mid-1880s, the Apache Kid had earned a reputation as one of the most dependable Indian Scouts in the Southwest. The Kid’s knowledge of the terrain and Apache tactics made him invaluable in tracking renegade bands.

1887 Incident

In May 1887, Seiber was called away on business and left the Kid in charge of the Indian Scouts and the guardhouse in San Carlos. What followed was a night that changed everything.

The scouts brewed tiswin—a potent, illegal drink made from fermented corn or fruit—and held a party. Drunken tempers flared, and tragedy struck.

During the chaos, a man named Gon-Zizzie killed the Kid’s father, Togo-de-Chuz. Though the Kid’s friends retaliated and killed Gon-Zizzie, the Kid’s fury wasn’t satisfied. Still burning with grief and rage, he rode to Gon-Zizzie’s home and murdered his brother, Rip.

That act—personal, brutal, and outside military justice—marked the end of the Apache Kid’s career as a scout. From that moment on, he was no longer a soldier. He was an outlaw.

On June 1, 1887, the Apache Kid returned to the San Carlos Reservation alongside four fellow scouts to give themselves up. Their arrival marked the beginning of a volatile chapter in frontier justice. Upon their return, the men were disarmed and confined to the guardhouse.

Tensions erupted when gunfire broke out, leaving Chief of Scouts Al Sieber wounded in the ankle—a crippling, lifelong injury. Although Seiber’s injury was blamed on the Kid, he was unarmed at the time. Fearing vigilante justice, the Kid and several others escaped amidst the chaos.

Surrender and Trial

Determined to recapture him, the Army dispatched troops who eventually tracked him to the rugged Rincon Mountains. But the Kid slipped away once more, this time sending a message to General Nelson Miles that he would surrender, but only if the cavalry were recalled. Miles agreed. On June 25, the Apache Kid surrendered.

What followed was a tangled legal affair. Neither the Kid nor his scouts could have fired on Seiber. They had already been disarmed before he was shot.

In the first trial, the Kid and his fellow scouts were found guilty of mutiny and desertion – not for the murder of his father’s killer or the attack on Seiber- and sentenced to death by firing squad. General Miles, disturbed by the severity of the verdict, intervened. He urged the court to reconsider, and the punishment was reduced to life imprisonment.

Still not satisfied, General Miles exerted his influence and had the punishment further reduced to a ten-year sentence. The men were transferred to Alcatraz.

Yet the case was far from over.

Conviction Temporarily Overturned

On October 13, 1888, the convictions were overturned. The ruling cited prejudice among the officers who had presided over the original court-martial. The Apache Kid and his companions were released as free men.

This decision ignited public outrage. To many settlers and military officials, the reversal was a betrayal of justice. To others, it was a rare moment of accountability within a system often stacked against Native scouts.

The Kid’s release didn’t just unsettle the frontier—it exposed prejudice in how justice was given or denied.

Second Trial and Conviction

By October 1889, a new warrant was issued in Gila County, charging the Apache Kid with assault for the wounding of Al Sieber during the 1887 guardhouse incident. The legal system, still determined to make an example of him, brought the Kid and several others to trial again.

On October 25, the verdict was handed down: guilty. The sentence was seven years in the Territorial Prison at Yuma.

The Kid would never arrive.

Escape

During the transport, the prisoners escaped. Somewhere along the rugged trail, they overpowered their guards, Sheriff Glenn Reynolds, Eugene Middleton, and W. A. Holmes.

Reynolds was killed in the struggle. Middleton was wounded. Holmes collapsed and died of a heart attack.

Later, Middleton would tell the story of how the Kid saved his life. One of the other Apache prisoners had raised a rock to finish him off, but the Kid stopped him. Mercy or self-preservation? Either way, it was an act that showed the Kid’s true personality.

The prisoners made their escape during a snowstorm, which erased their tracks. The Kid and his companions vanished into the wilderness.

It was the last official sighting of the Apache Kid and the beginning of his legend.

Fugitive Status

After his escape in 1889, the Apache Kid seemed to dissolve into myth. Rumors swirled across the Southwest: some claimed he led a small band of renegades, raiding ranches and freight lines from Arizona to northern Mexico, vanishing into the Sierra Madre Mountains like smoke.

Others whispered he had become a lone wolf—feared by white settlers, shunned by his own people. Though some newspapers of the time claimed that he was responsible for dozens of murders, there is little credible evidence to substantiate those claims.

The Arizona Territorial Legislature placed a $5,000 bounty on his head, dead or alive. No one ever claimed it.

By 1894, the trail went cold. Reports of raids ceased. Had the Kid died? Or simply retired into the wilderness?

Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky of the Mexican Rurales claimed to have seen him alive in the Sierra Madre in 1889. Others believed he succumbed to tuberculosis. Some said Apache vigilantes had executed him in secret. The truth remained elusive.

Unknown Death

No one could agree on when—or where—the Apache Kid died. One Mormon tale tells of his killing at the hands of settlers. This was supposedly after he had kidnapped and murdered several Mormon women. Another legend says his name foretold his fate: a man of mystery, destined to vanish.

High in the San Mateo Mountains of New Mexico, a gravesite memorial stands in the Cibola National Forest. Local lore says a vengeful posse caught up with the Kid there, killed him, and hacked a blaze into a nearby tree—a scar still visible today.

The grave lies one mile northwest of Apache Kid Peak, at Cyclone Saddle.

An interesting side note to the Kid’s legend is that one of the U.S. Cavalry soldiers who hunted for the Kid was the future novelist Edgar Rice Burroughs, famous for creating Tarzan. In 1933, he wrote a novel titled Apache Devil.

Despite the title, it was a sympathetic book that highlighted the heartbreaking lives of the Apache during that era. Many thought it was based on the life of the Apache Kid.

Sources:

Hutton, Paul Andrew. “Legend of the Apache Kid.” HistoryNet, 27 February 2017, https://www.historynet.com/legend-apache-kid/

Turner, Jim. “What history writes about the Apache Kid.” Globe Miami Times, 4 May 2010, https://www.globemiamitimes.com/stories/what-history-writes-about-the-apache-kid,72829

Weiser-Alexander, Kathy. “The Apache Kid – Outlaw Legend of the Southwest.” Legends of America, Updated December 2024, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-apachekid/

Sanchez, Linda A. “The Final Nail in the Apache Kid’s Coffin.” True West, 21 January 2019, https://truewestmagazine.com/article/the-final-nail-in-the-apache-kids-coffin/

Conliffe, Ciaran, “The Apache Kid, Soldier and Outlaw.” HeadStuff, 19 July 2016, https://headstuff.org/culture/history/the-apache-kid-soldier-and-outlaw/

Great story. Thanks for putting it out. I had not heard of the Apache Kid. More needs to be written.