A Father Framed: The Unjust Execution of Timothy Evans

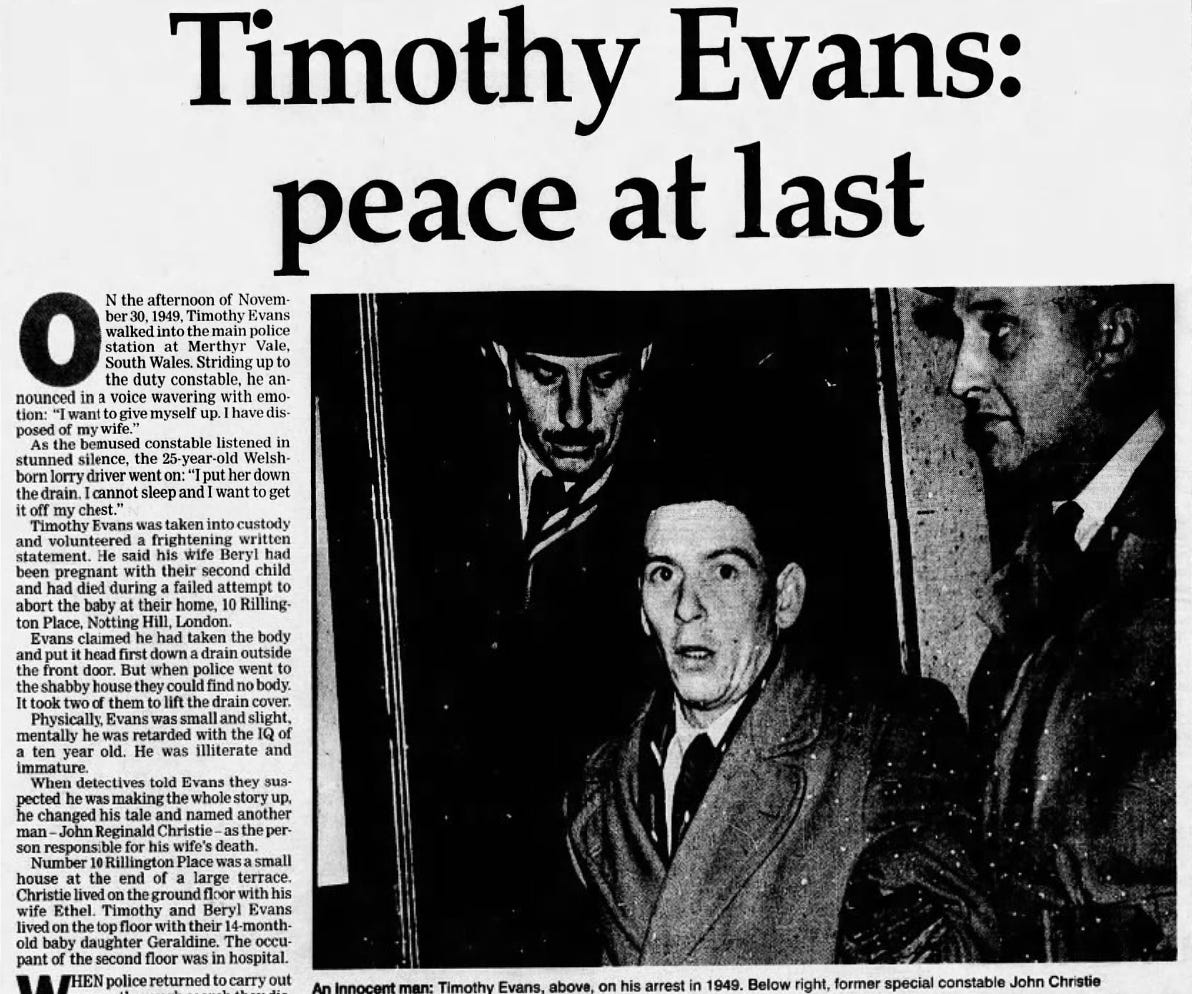

In March 1950, 25-year-old Timothy Evans was hanged for the murder of his daughter. Three years later, it was revealed that he had been framed by his murderous neighbor

Background

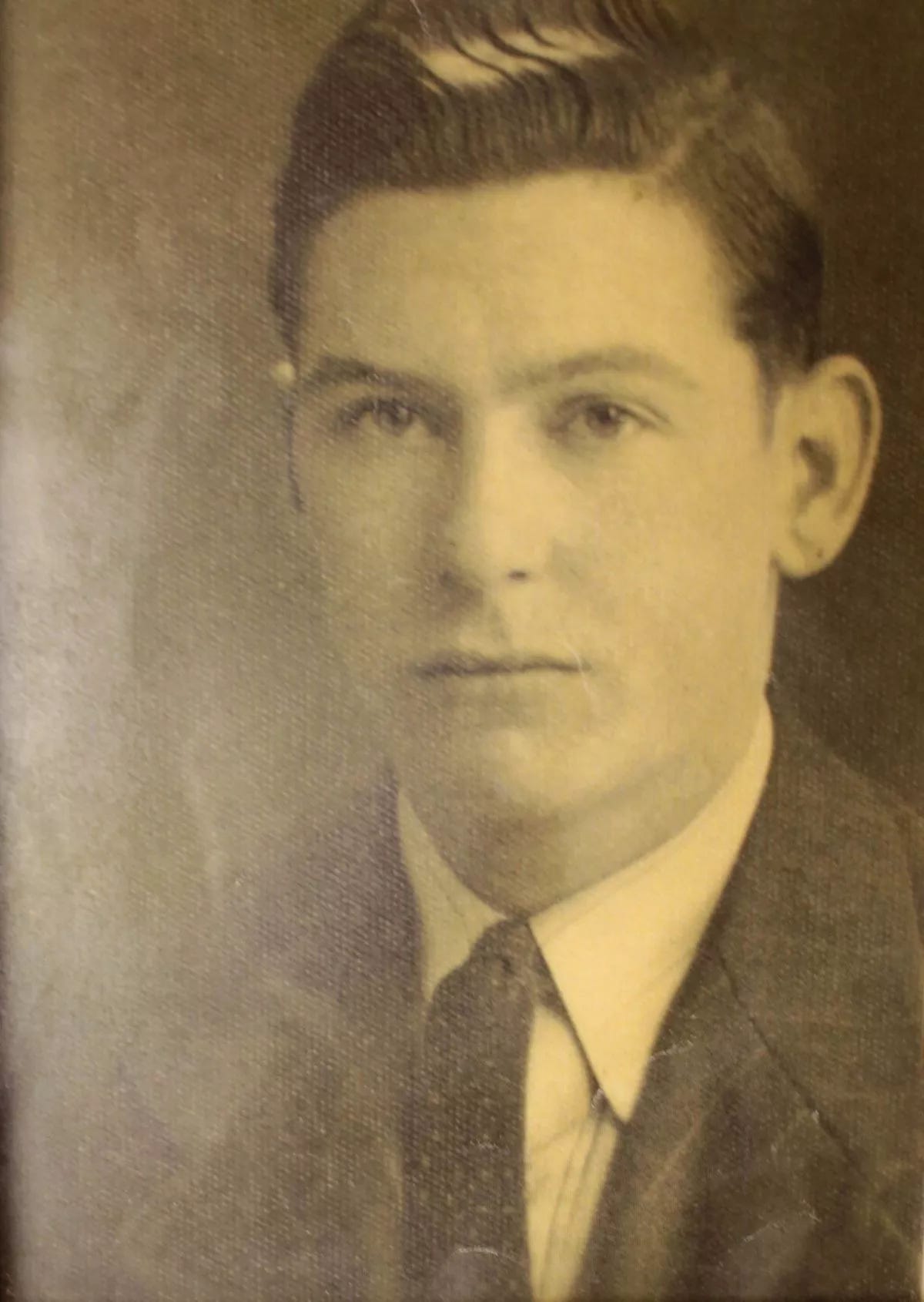

In the dim, soot-stained streets of post-war London, where ration lines stretched around corners and the city still wore its bomb scars like open wounds, a young man named Timothy Evans walked daily past the rented room in a crumbling terrace house at 10 Rillington Place, which he shared with his wife and infant daughter. Work bag in hand, trying, in his own modest way, to build a life.

Three years later, he would be buried in an unmarked prison grave, hanged for a crime he likely did not commit, while the true murderer watched from the shadows.

A Quiet Struggle

Timothy John Evans was born into poverty in 1924 in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. He left school early and struggled with literacy all his life. Evans was known to exaggerate stories and often tried to appear more capable than he was. His speech was marked by a stammer which worsened under pressure, and he had difficulty articulating himself, especially when nervous.

In 1947, he married Beryl Thorley, a bright and hopeful young woman. Their early married life was marked by financial hardship, frequent arguments, and the looming challenge of raising a family in the post-war economy.

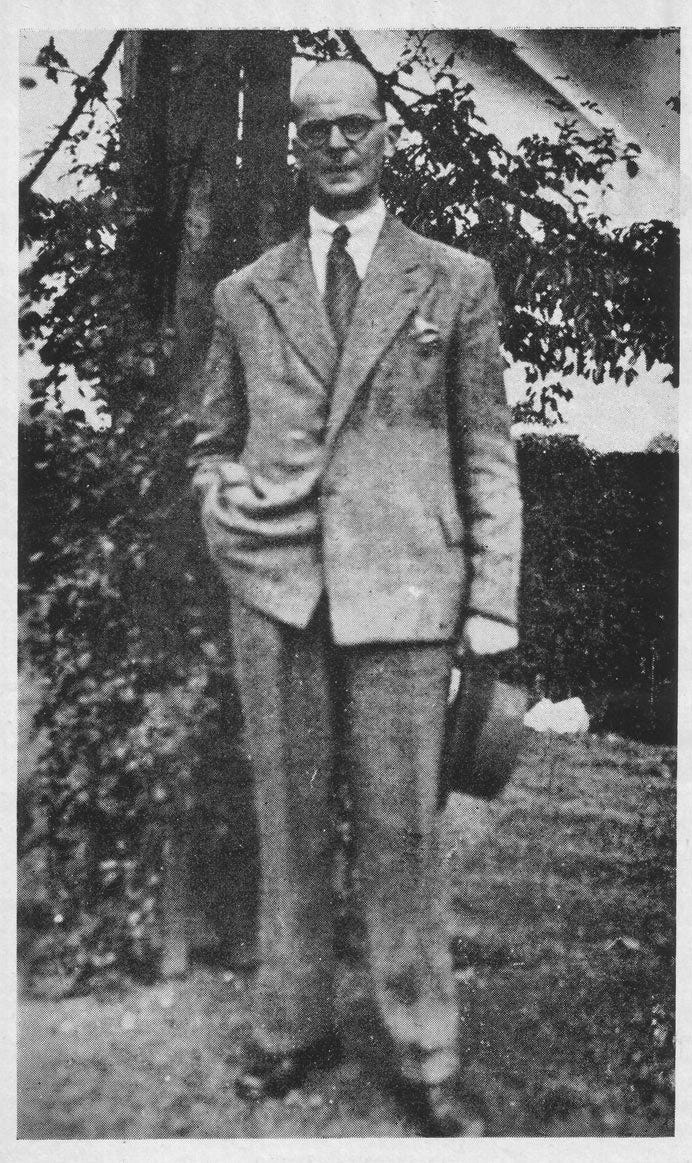

They moved to London, eventually taking the top-floor flat at 10 Rillington Place, a decaying building in Notting Hill that they shared with other tenants. Below them lived John Christie and his wife, Ethel, an unassuming older couple who kept to themselves. Christie, a former special constable, often offered advice and support to younger tenants.

A Desperate Situation

In 1949, Beryl and Timothy Evans were barely surviving. Though young and hopeful at the start of their marriage, the pressures of post-war life quickly set in. Money was scarce, arguments and fights frequent, and their surroundings bleak. Beryl discovered she was pregnant again.

At the time, abortion was illegal in the United Kingdom under almost all circumstances. It was rarely discussed openly, and access to safe procedures was nearly impossible for working-class families.

Yet, for Beryl and Timothy, another child felt unthinkable, as they were already struggling to feed and care for their daughter, Geraldine. Beryl confided to neighbors that she was terrified at the prospect of another baby, as they simply couldn’t afford it. These circumstances led them to make a desperate decision: they would seek an abortion.

That’s when John Christie, their downstairs neighbor, offered to help. Christie claimed he had medical experience from his time as a war medic and that he had assisted in similar situations before.

To a frightened couple with no money, little education, and few options, Christie’s offer may have felt like a lifeline. This moment of vulnerability, born out of fear and poverty, would prove fatal for Beryl, and eventually for Timothy and Geraldine as well.

The Confessions

On November 30, 1949, Timothy Evans walked into a police station in Merthyr Tydfil and told officers that his wife had died under unusual circumstances. His first confession was halting and unclear: he claimed to have accidentally killed Beryl by giving her a substance to induce an abortion, something, he said, that had been supplied by “a man.” He then disposed of her body in a drain outside their home.

But when police examined the manhole in front of 10 Rillington Place, they found nothing. In fact, the cover was so heavy that it took the strength of three officers to remove it. Evans’ story didn’t add up. When questioned further, Evans altered his statement - this time, he implicated John Christie.

Evans explained that Christie had offered to help perform an abortion, something Evans had avoided mentioning earlier to protect Christie, as abortion was illegal in the UK at the time. After some deliberation, Evans said, he and Beryl agreed to let Christie proceed.

On November 8, Evans returned from work, and Christie informed him that the procedure had failed and that Beryl was dead.

Evans said that Christie promised to dispose of the body and claimed that a couple from East Acton would adopt and take care of Geraldine. On November 14, Evans left for Wales as instructed. He later returned to London, concerned about his daughter, but Christie refused to allow him to see her.

On December 2, police searched the property surrounding 10 Rillington Place. There, they discovered the body of Beryl Evans wrapped in a tablecloth, hidden in a wash-house in the back garden. Next to her lay the body of Geraldine. Both of them had been strangled.

Though Evans seemed surprised to hear that his daughter was dead, during questioning, he confessed to the murders. However, he later claimed that he feared he would be subjected to violence by the police if he did not confess.

Trial and Execution

Evans’s trial began in January 1950 at the Old Bailey. It lasted three days and focused exclusively on the murder of Geraldine, not Beryl. The prosecution argued that Evans had killed his daughter to eliminate a witness after murdering his wife.

The defense tried to present the version of events in which Christie had been the central figure in the deaths, but it struggled against Evans’s changing statements. Evans took the stand, but his stammer, poor memory, and visible distress undermined his credibility.

His confused explanations stood in stark contrast to the cool, measured testimony of John Christie, who portrayed himself as a helpful neighbor caught in a tragic situation.

The jury deliberated for just 40 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. On March 9, 1950, 25-year-old Timothy Evans was hanged at Pentonville Prison. Evans went to the gallows maintaining his innocence, particularly concerning the death of his daughter.

At the time, there was little public outcry - Evans was seen as a troubled, perhaps mentally unstable man; his confessions, though inconsistent, seemed to confirm his guilt. The notion that he had been manipulated, or that someone else might be responsible, received little attention.

The Truth Revealed

After Timothy Evans was hanged in 1950, life at 10 Rillington Place seemed to return to a strange kind of normalcy. John Christie continued to live at the property; he remained in the downstairs flat with his wife, Ethel, and even took on work as a clerk and postman, but behind the closed doors of the dingy terrace house, something dark was festering.

By early 1953, Christie had fallen into financial trouble - he was unemployed, struggling to pay rent, and increasingly isolated. Then, without warning, he told neighbors that his wife had gone to visit relatives. In truth, Ethel was dead, strangled by Christie, likely in December 1952. Her body was buried beneath the floorboards of the front room.

Christie began subletting the flat to make ends meet, but his strange behavior alarmed the new tenants. He insisted that the kitchen was off-limits and refused to let anyone use the garden. Suspicion grew, and in March 1953, Christie abruptly left the property, taking only a small suitcase and telling neighbors he was going away for work.

The landlord, needing to prepare the flat for new occupants, sent in workmen to clean. On March 24, 1953, one of the workers noticed a loose panel in the kitchen wall. Behind it was a small, foul-smelling alcove. Inside, in a crouched tangle, were the decomposing bodies of three women. Ethel’s body was found beneath the floorboards, and two more skeletons were located in the back garden.

Arrest of John Christie

A manhunt for John Christie was launched across London. He had been sleeping rough, moving from lodging houses to embankments, blending in with the city’s transient poor.

On March 31, 1953, Christie was finally arrested near Putney Bridge after being recognized by a policeman; he was calm and cooperative as officers took him into custody, and he reportedly remarked, “I suppose you’ll be glad to have me.”

After being convicted for the murder of his wife, Ethel, John Christie was hanged in July 1953.

Aftermath

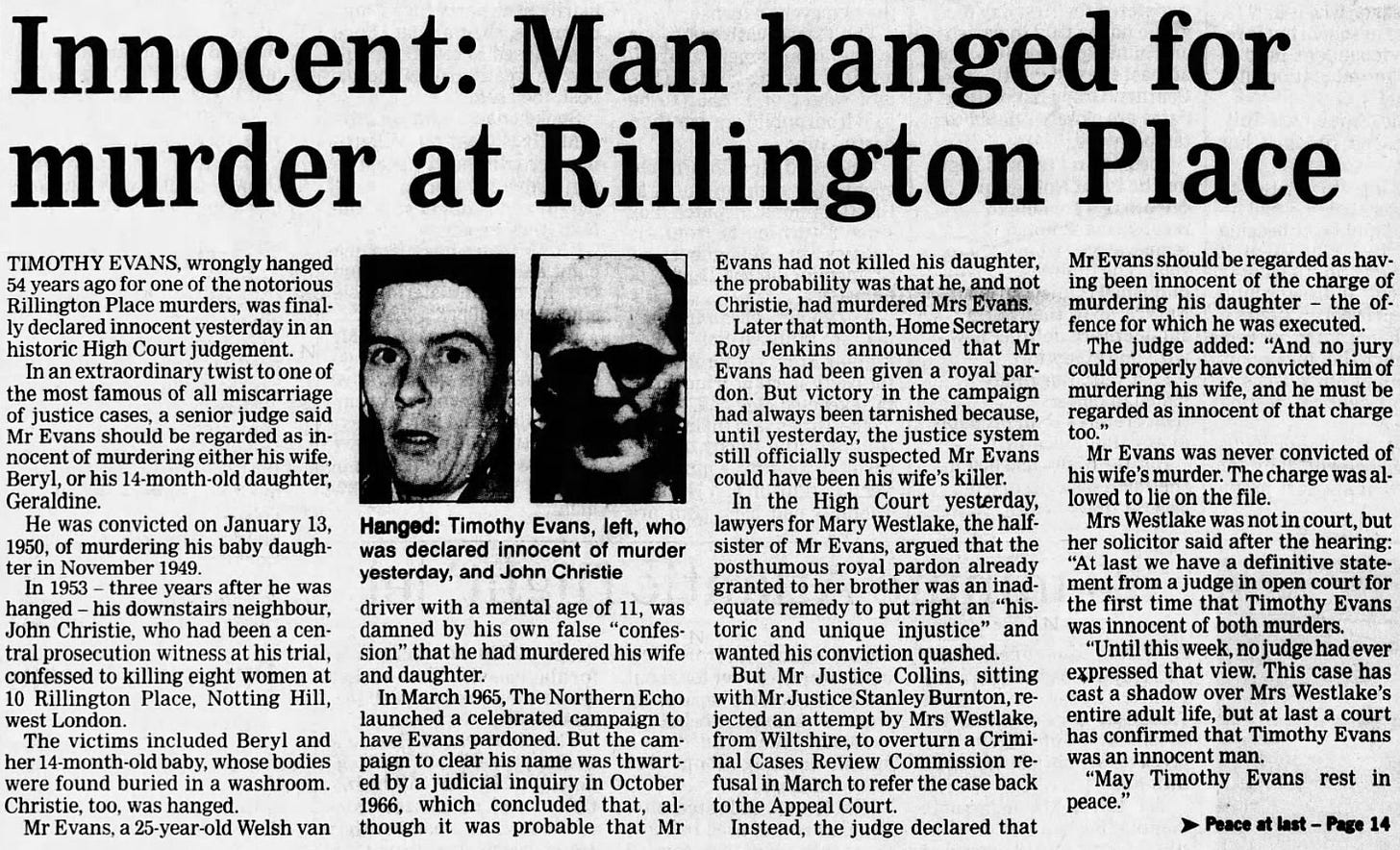

After several inquiries into the matter, in 1966, Timothy Evans was granted a posthumous pardon for Geraldine’s murder, though not a formal acquittal; the pardon was a powerful public recognition of the miscarriage of justice that had occurred.

The case of Timothy Evans became one of the defining legal scandals of 20th-century Britain. It contributed directly to the growing unease around the death penalty and helped prompt its abolition in 1969.

His story remains a chilling reminder of how vulnerable individuals—especially those without education, money, or support—can be overwhelmed by the machinery of the justice system.

Sources:

Carradice, Phil, “The execution of Timothy Evans”, BBC, Monday 16 January 2012, https://www.bbc.co.uk/webarchive/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.co.uk%2Fblogs%2Fwales%2Fentries%2Fcdc56160-91eb-366d-ae0e-5d9c5a676fe2

Made in Manchester (MIM) “The Tragic Life and Death of Timothy Evans”, https://www.madeinmanchester.tv/timothy-evans

Jacobson, Stephanie, “Crime of the Century: The Case of Timothy Evans”, September 17, 2021, https://home.heinonline.org/blog/2021/09/crime-of-the-century-the-case-of-timothy-evans/

The case inspired the movie "10 Rillington Place", starring Richard Attenborough.

Thank you sharing, it was quite an interesting read.